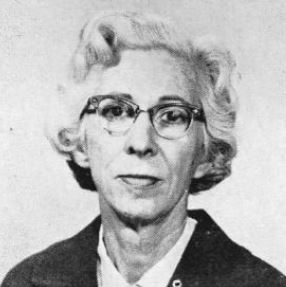

The sexual abuses suffered during a seven-month period from 1984-1985 by 51 students at the Wee Care Day Nursery in Maplewood, N.J., led to a widely publicized trial and 1987 conviction of teacher Margaret Kelly Michaels. For seven months Margaret Kelly Michaels, a 22-year-old teacher's aide at Wee Care, had been sexually abusing the girl and her classmates. The child's mercurial behavior suddenly made sense. Defendant, Margaret Kelly Michaels, appeals from her jury conviction on 115 counts of sexual offenses involving twenty children who were in the Wee Care Nursery School (Wee Care). The trial court sentenced defendant to an aggregate term of forty-seven years in prison, with fourteen years of parole ineligibility, and $2,875 in fines payable to.

Wee Care Nursery School, located in Maplewood, New Jersey, was the subject of a day carechild abuse case that was tried during the 1980s.[1][2] Although Margaret Kelly Michaels was prosecuted and convicted, the decision was reversed after she spent five years in prison. An appellate court ruled that several features of the original trial had produced an unjust ruling and the conviction was reversed.[3] The case was studied by several psychologists who were concerned about the interrogation methods used and the quality of the children's testimony in the case.[4] This resulted in research concerning the topic of children's memory and suggestibility, resulting in new recommendations for performing interviews with child victims and witnesses.[5][6]

Accusation[edit]

In April 1985, a nurse took the temperature of a 4-year-old boy with a rectal thermometer and the boy said, 'That's what my teacher does to me at nap time at school.' The comment was reported to the local authorities, and all the children at the Wee Care Nursery School were questioned.[7] Social workers and therapists collected testimony from 51 children from the day care center. During the interviews, children made accusations such as that Michaels forced them to lick peanut butter off of her genitals, that she penetrated their rectums and vaginas with knives, forks and other objects, that she forced them to eat cakes made from human excrement and that she made them play duck, duck, goose while naked. Michaels was indicted for 235 counts of sexual offenses with children and youths.[3] She denied the charges.[8]

Upon conviction, when asked whether they actually believed some of the more sordid claims from the children, prosecutors Glenn Goldberg and Sara McArdle answered 'No' and 'Oh, absolutely' simultaneously.[9] But when journalist Dorothy Rabinowitz asked about some of these bizarre elements, such as knives that left no scars, Goldberg replied, 'What is there left to know? The jury has spoken. She's convicted.'[10]

Trial[edit]

The trial began on June 22, 1987.[3] 'The prosecution produced expert witnesses who said that almost all the children displayed symptoms of sexual abuse.'[11] Prosecution witnesses testified that the children 'had regressed into such behavior as bed-wetting and defecating in their clothing. The witnesses said the children became afraid to be left alone or to stay in the dark. They also testified that the children exhibited knowledge of sexual behavior far beyond their years.'[11] Some of the other teachers testified against her.[11] The defense argued that Michaels had not had the opportunity to take the children to a location where all of the alleged activities could have taken place without being noticed.[11] The jury was not shown the transcripts of the interrogations of the children that produced the accusations.[10]

After nine months, the case went to the jury for deliberation. At that time, 131 counts remained, including charges of aggravated sexual assault, sexual assault, endangering the welfare of children, and making terroristic threats. The jury deliberated for 12 days before Michaels was convicted of 115 counts of sexual offenses involving 20 children.[3][12]

Margaret Kelly Michaels Today Thirty Years Later

On August 2, 1988, Michaels was sentenced to 47 years in prison, with no possibility for parole for the first 14 years.[3] The judge 'said the facts in the case were sordid, bizarre and demeaning to the children.'[13] Michaels 'told the judge that she was confident her conviction would be overturned on appeal.'[13]

Release[edit]

In March 1993, after five years in prison, Michaels' appeal was successful and she was released.[3] The New Jersey Supreme Court overturned the lower court's decision and declared 'the interviews of the children were highly improper and utilized coercive and unduly suggestive methods.' [14]

A three-judge panel ruled she had been denied a fair trial because 'the prosecution of the case had relied on testimony that should have been excluded because it improperly used an expert's theory, called the child sexual abuse accommodation syndrome, to establish guilt.'[15] In June 1993, the State Supreme Court refused to hear the prosecutor's appeal of the decision.[16]In February 1994, 'the court heard arguments...about the admissibility of evidence.' [1]

In December 1994, the prosecution dropped the attempt to retry the case 'because too many obstacles had been placed in the way of a successful retrial.'[17] The major hurdle was that 'if the state decided to reprosecute Michaels, it must produce 'clear and convincing evidence' that the statements and testimony elicited by the improper interview techniques are reliable enough to warrant admission.'[17][18] 'While the Supreme Court stopped short of instructing the prosecutor to drop the case, the court made it clear that it believed the children's testimony would not hold up.' [17]

Interrogation methods[edit]

During Michaels’ appeal, researchers Maggie Bruck and Stephen Ceci prepared an amicus brief regarding the case that pointed out several problems with the children's testimony that was the primary evidence. Some of the issues that were addressed were the role of interviewer bias, repeated questions, peer pressure, and the use of anatomically correct dolls in contaminating the children's testimony. These interview techniques could have led to memory errors or false memories. In addition to the problems with the interviews themselves, the fact that there were no recordings of initial interviews meant that important evidence was missing; therefore, it was not possible to determine the origin of some of the information that children reported (i.e., it could have been suggested to them by interviewers in the early interviews.[4]

Interviews from the Wee Care Nursery School and McMartin preschool trials were examined as part of a research project on the testimony of children questioned in a highly suggestive manner. Compared with a set of interviews from Child Protective Services, the interviews from the two trials were 'significantly more likely to (a) introduce new suggestive information into the interview, (b) provide praise, promises, and positive reinforcement, (c) express disapproval, disbelief, or disagreement with children, (d) exert conformity pressure, and (e) invite children to pretend or speculate about supposed events.'[19]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ abSullivan, J. (February 4, 1994). 'In Retrying Abuse Case, A New Issue'. New York Times. Retrieved 2007-01-21.

Just how to prevent fantasy from being presented as fact in sex-abuse cases is facing the New Jersey Supreme Court in the wake of one of the most sensational of the spate of cases involving day-care workers during the 1980's. The court heard arguments today about the admissibility of evidence in the case of Margaret Kelly Michaels, who was convicted of sexually molesting 19 children, many of them 3- and 4-year-olds, during her seven-month employment at Wee Care Nursery in Maplewood. She served 5 years of a 47-year sentence before her conviction was overturned early last year.

CS1 maint: discouraged parameter (link) - ^'Nightmare at the Day Care: The Wee Care Case'. Crime Magazine. Retrieved 2007-08-21.CS1 maint: discouraged parameter (link)

- ^ abcdefState of New Jersey v. Margaret Kelly Michaels (1993). 264 N.J. Super. 579; 625 A.2d 489

- ^ abBruck, Maggie; Ceci, Stephen J. (1995). 'Amicus brief for the case of state of New Jersey v. Michaels presented by committee of concerned social scientists'. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law. 1 (2): 272–322. doi:10.1037/1076-8971.1.2.272.

- ^La Rooy, David. 'As the Vatican is confronted by the UN we must remember that the best evidence in child abuse cases will come from the victims themselves'. The Independent. Retrieved 2014-02-08.CS1 maint: discouraged parameter (link)

- ^Lamb, M.E.; Orbach, Y.; Hershkowitz, I.; Esplin, P. W.; Horowitz, D. (2007). 'A structured forensic interview protocol improves the quality and informativeness of investigative interview with children: A review of research using the NICHD investigative interview protocol'. Child Abuse and Neglect. 31 (11–12): 1201–1231. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2007.03.021. PMC2180422. PMID18023872.

- ^'The Kelly Michaels Case'. University of Missouri-Kansas City School of Law. Retrieved 2007-08-26.CS1 maint: discouraged parameter (link)

- ^Narvaez, A. (February 28, 1988). 'Former Day-Care Teacher Denies Sexually Abusing Schoolchildren'. New York Times. Retrieved 2007-01-21.CS1 maint: discouraged parameter (link)

- ^Rabinowitz, Dorothy (March 27, 2003). 'Epilogue to a Hysteria: Did prosecutors really believe their phony child-abuse charges?'. Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 2004-12-17.

- ^ abRabinowitz, Dorothy (April 28, 2003). 'The Sacrosanct Accusation: No questions, they told me about phony sex-abuse charges. I asked anyway'. Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 2004-12-17.

- ^ abcdNarvaez, A. (March 29, 1988). 'Legal Arguments End in Jersey Child-Abuse Trial'. New York Times. Retrieved 2007-01-21.

Legal arguments in the nine-month trial of a day-care teacher accused of sexually abusing 20 children at a center in Maplewood ended here today.

CS1 maint: discouraged parameter (link) - ^'Abuser or Abused? : Ruling Triggers Questions over Who's Real Victim in N.J. Molestation Case'. 20 April 1993.

- ^ abRangel, J. (June 3, 1994). 'Ex-Preschool Teacher Sentenced to 47 Years in Sex Case in Jersey'. New York Times.

- ^Seth Mydans (June 3, 1994). 'Prosecutors Rebuked in Molestation Case'. New York Times. Retrieved 2007-08-21.CS1 maint: discouraged parameter (link)

- ^Fiason, F. (March 27, 1993). 'Child-Abuse Conviction Of Woman Is Overturned'. New York Times. Retrieved 2007-01-21.CS1 maint: discouraged parameter (link)

- ^'Court Rejects Bid to Restore Abuse Verdict'. New York Times. June 10, 1993. Retrieved 2007-01-21.CS1 maint: discouraged parameter (link)

- ^ abcNieves, E. (December 3, 1994). 'Prosecutors Drop Charges In Abuse Case From Mid-80's'. New York Times. Retrieved 2007-01-21.

Ending one of the most sensational child sex-abuse scandals in the nation, prosecutors today formally dropped their case against Margaret Kelly Michaels, the former day care teacher who spent five years in prison before her 1987 conviction was overturned on appeal last year.

CS1 maint: discouraged parameter (link) - ^'IPT Journal - 'State v. Michaels: A New Jersey Supreme Court Prescription for the Rest of the Country''. www.ipt-forensics.com.

- ^Schreiber, Nadja; Lisa Bellah, Yolanda Martinez, Kristin McLaurin, Renata Stok, Sena Garven and James Wood (2006). 'Suggestive interviewing in the McMartin Preschool and Kelly Michaels daycare abuse cases: A case study'. Social Influence. Psychology Press. 1 (1): 16–46. doi:10.1080/15534510500361739. S2CID2322397.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

External links[edit]

Margaret Kelly Michaels Today Thirty Years Lateral

- Wee Care Nursery School at the Ontario Consultants on Religious Tolerance

Margaret Kelly Michaels Today Thirty Years Lateralis

Front entrance of Comet Ping Pong pizzeria, a restaurant in Washington, D.C., that’s been at the center of a media conspiracy theory involving child sex abuse rings. Photo by Alex Wong/Getty Images

Pizzagate, a nutty conspiracy theory about a child sex ring run from a Washington, D.C., pizzeria, has become the focal point for the “fake news” alarm—particularly after a rifle-toting man recently showed up at the restaurant to “self-investigate” and rescue nonexistent victims. While no one was injured, the incident lent an eerie prescience to an earlier Washington Posteditorial titled, “ ‘Pizzagate’ shows howfake news hurts real people.” The politics of Pizzagate—mostly pushed by Donald Trump supporters (including Michael J. Flynn, son of Trump’s national security adviser-to-be Michael T. Flynn) and purported to implicate Hillary Clinton and her campaign chief John Podesta—make it even more emblematic of the “fake news” issue. To many pundits, this is terrifying evidence of the dark irrationality unleashed by the Trump campaign.

The Pizzagate saga is indeed disturbing. An obscure reference in one of Podesta’s hacked emails—a handkerchief with “a map that seems pizza-related”—was somehow deemed a code for child sex. From there spun a web of wild allegations with everything thrown in: an Instagram joke about restraining unruly children with tape; heart- and butterfly-shaped images supposedly resembling pedophilic symbols; the name of pizzeria owner, James Alefantis, is said to be rearranged from the French J’aime les enfants (“I love children”). The restaurant, Comet Ping Pong, received a barrage of threatening phone calls and online messages even before the visit from the gunman; the harassment also spread to neighboring businesses.

Is it scary that people’s lives can be severely disrupted, even endangered by baseless, zealotry-driven accusations of evil acts? Of course. Is this a danger uniquely linked to “fake news” and online vigilantes with a right-wing bent? Fairly recent history suggests otherwise.

In the 1980s and 1990s, a wave of notorious cases involving allegations of ritual child sex abuse rings in day care centers swept the country. In California, the infamous McMartin Preschool case dragged on for six years before its ignominious end in 1990. (The trial ended with one defendant acquitted and the other—Ray Buckey, the sole male defendant—acquitted on most counts with the jury deadlocked on a few more. All charges against five other accused employees had been dismissed earlier.)

The McMartin case began with accusations made by a mother suffering from paranoid schizophrenia whose allegations quickly escalated to madhouse material: A few months after her initial police report, she was claiming that her son had his ears and tongue stapled, that children were forced to drink the blood of a slaughtered infant and that Buckey “flew through the air.” Before long, small children were coaxed into telling fantastical tales of grotesque sexual acts, Satanic rites and animal sacrifice, often taking place in secret tunnels underneath the preschool, at other times in car washes and churches.

And where were the professional news media? Falling for it hook, line and sinker. Later, in 1990, Los Angeles Times reporter David Shaw won a Pulitzer Prize for a multipart series that offered a devastating analysis of the McMartin media coverage, including that of his own paper. Among the faults of the press, he listed “pack journalism,” “laziness,” excessive coziness with the prosecution (Wayne Satz, the reporter covering the case for the local NBC News station was quite literally in bed with Kee MacFarlane, the social worker in charge of the children’s interviews) and “a competitive zeal that sends reporters off in a frantic search to be first with the latest shocking allegation.” As a result, Shaw wrote, “Reporters and editors often abandoned two of their most cherished and widely trumpeted traditions—fairness and skepticism,” instead embracing “hysteria, sensationalism and what one editor calls ‘a lynch-mob syndrome.’ ”

Margaret Kelly Michaels Today

Alas, this was typical of how the media treated the bogus day care sex abuse cases. In New Jersey in 1987, 25-year-old kindergarten teacher Margaret Kelly Michaels was convicted on charges that included forcing 3- and 4-year-olds into naked orgies, raping them with utensils, urinating on them and making them eat her feces. (The children’s “disclosures” were elicited under highly coercive questioning, in an investigation triggered by one little boy’s misconstrued comment.) These horrors were utterly improbable given the lack of physical evidence and lack of privacy in the room where Michaels supposedly committed her crimes. Yet once again, media skepticism was absent. It took two journalists outside the political mainstream—Dorothy Rabinowitz of the Wall Street Journal on the right, Debbie Nathan on the left—to raise obvious questions about the case. Michaels spent five years behind bars, out of a 47-year sentence, before her conviction was overturned on appeal.

The 1980s sex abuse panic was a mainstream hysteria while Pizzagate is a fringe one; but the two have uncanny similarities. In both cases, things ranging from innocuous to eccentric to mildly inappropriate got recast as suggesting pedophile proclivities—particularly if they could be seen as sexually “creepy.” Today, Pizzagate “sleuths” find it incriminating that Comet Ping Pong, an offbeat arty venue, has had weird murals with abstract nudes and that some of its employees’ Instagram accounts have featured bawdy (non–child-related) cartoons. Thirty years ago, Buckey and Michaels were portrayed as perverts because he sometimes wore loose shorts with no underwear and she had scribbled a vaguely erotic poem in her notebook.

The child sex abuse panic of the 1980s is also a reminder that paranoia about pedophiles is hardly the sole province of right-wing nuts. While some of the fears about devil worship were driven by religious fundamentalism, feminists who saw hidden child rape as an intrinsic part of patriarchal violence played a major role in ritual abuse scare. (They were even more involved in the closely related bogus moral panic about recovered memories of incest, also treated with excessive credulity by the mainstream media until the early 1990s.) Indeed, MacFarlane, one of principal malfeasants in the McMartin fiasco, had started out as a feminist activist before turning child abuse crusader.

During the McMartin case, in 1989, the Los Angeles County Commission on Women launched a Ritual Abuse Task Force headed by feminist psychotherapist Myra Riddell. Women’s liberation doyenne Gloria Steinem not only endorsed a 1990 recovered-memory manual that encouraged women to see everything from arthritis to trust issues as symptoms of forgotten abuse but helped fund a futile quest for evidence of guilt in the McMartin case. And as late as 1993, Ms. magazine ran a lurid cover story purporting to be a survivor’s account, headlined, “Ritual Abuse Exists—Believe It!”

So let us by all means decry the conspiracy theories and the “fake news” of today. But we would do well to remember that even real journalists and cultural progressives are not immune to absurd claims of pedophile conspiracies when the right buttons get pushed. And as much as one can sympathize with innocent people harassed and threatened because of Pizzagate, the plight of innocents imprisoned on horrific made-up charges was far worse.